Jordan Charlton: What is your poetic story? How long have you been writing poems?

Jessica Poli: I have poetry journals as far back as fifth grade, and other journals further back than that. But I started writing poetry seriously in undergrad when I was at the University of Pittsburgh. I took a couple of classes with CM Burroughs, a wonderful poet, and she really encouraged me and said, you know, this is a thing you could do, which, up until that point, I hadn't realized it was a “thing” people could actually “do” and shape their life around and potentially make a living with. She encouraged me to apply to MFA programs, which I did. I did my MFA at Syracuse University, and then came here to Nebraska. I don't know if I have a “real” answer to why I started writing poetry. I liked it. I was drawn to it. I don't know why we initially get drawn to certain things. I don't know why someone picks up a violin, or why my mom's a painter—but that's the thing she loves. And this is the thing I ended up loving. I write in other genres sometimes, but I always come back to poetry. I have reasons now, but that has nothing to do with the initial impulse, which was mysterious.

JC: Mysterious, right. It's a thing that you love, and we have to talk about love when we talk about Red Ocher. There's this really gorgeous introduction by Patricia Smith, where she writes that poems should…

JP: Vivify!

JC: Vivify! Yes. And create a shift in the chest, be a world-changing-type thing. In your process of writing this book, who were some of the people who shifted your world or rattled something in your chest?

JP: I was thinking of the centos in Red Ocher as I was trying to formulate my answer. One of the first people who comes to mind is Sylvia Plath. She was one of the first writers I ever fell in love with. I remember reading her in high school, maybe even middle school, and just being completely engaged and drawn in, reading The Bell Jar and her diaries. When I started getting more serious about writing poetry, I started reading her poetry and came across “Sheep in Fog,” which remains one of my favorite poems. There are a few lines of hers in the centos, which is really cool. The centos were a wonderful project for me in that I got to spend so much time deeply engaged with writers whom I love. To answer the question of who are the writers who have made an impact on me, a lot of them are in those centos.

JC: What drew you to that form?

JP: I started it as an exercise. I never meant it to be something that was going to be published or included in the book. I started writing centos as a personal exercise to think about the line and what it's capable of. What it can do. That is an exercise I really encourage because I think it's a great way to really think closely about what the line as a unit can do, and what can change just based on a line break. It really got me to think of lines as their own individual entities that you can then play with.

JC: When trying to craft a Cento, do you typically gravitate to a line that inspires you first or a subject?

JP: A line. Definitely a line. I had a whole document going of lines that I had been drawn to. I went from there and sort of treated it like a puzzle. I was just thinking about beginning at the beginning, asking what is the first line going to be, and then really thinking in sequential order. I think that for a cento to really succeed, it should have something unifying about it—a logic, a tone, a voice that holds each line together. That's big. And that's hard. I struggled a lot with that throughout most of them. I would start with looking at what is the first line and then start hunting for the next line. And sometimes I would find that in that big document that I had going. Other times, I would just have to start flipping through books, and really thinking about grammar and syntax—then, after making sure the sentence itself made sense, I’d consider content, tone, voice.

JC: That sounds really genius. Can you speak a little bit about when you feel like you know that “puzzle” is done?

JP: It feels like the same question as knowing when a poem is done. And the answer for me is you feel it. I don't think there's an easy answer to that question. I think it's something you know intuitively because you have been so immersed in the making of the thing that once it's done, you know it is.

JC: Red Ocher features a litany of poetic forms. From aubades to Centos, which we've spoken a little bit about. I think there's at least one Ghazal in there, too. Rich in its poetic variety, Red Ocher offers a thoughtful glimpse into the poetic world while tackling subjects of love and loss, things that are familiar to many people. It’s a wonderful collection to incorporate in an introductory creative writing class. Or a poetry workshop. Can you speak to what brought you to all these forms?

JP: I think there were particular forms that seemed to lend themselves really well to the subjects that I was working on. And a lot of that had to do with their use of repetition, which felt like something that made sense to me, and made sense in how I was thinking through the things I was writing about, especially all of the “failed love” poems. Because within those situations or relationships, there were a lot of circling thoughts, a lot of cycling through the same worry or obsession. What did I do wrong? What could I have done differently? That sort of anxiety. I felt that in the forms, like in the ghazal, in the pantoum, there was this circling back and back and back to the same thing. And at times, there is not really a feeling like you're getting anywhere. By the end of those poems, I think I do get somewhere different than where I was at the beginning. And so that was almost comforting to me, writing those, because I think, subconsciously, that made me realize, okay, there's a way out of this. There’s a way out of this cycle of intrusive thoughts.

JC: I love that, and I do want to talk about feelings. Jess, you've also written four chapbooks as well. What feels different this time around for you? What feels new?

JP: Those chapbooks felt easier in a lot of ways. They're shorter. You don't have as much that you need to hold in your mind when you're putting them together. Even in terms of organizing a collection, you might sit down and say, I have this pile of poems, what am I going to do with them? One thing we poets often do is, you know, print them out, put them on the wall, lay them out on the floor, right? So logistically, it's just a harder task. I like to think about collections visually. I like to think about what they're doing, from beginning to end, visually. That was harder to do with a full-length collection. I went through many different iterations of ordering the poems and putting them in sections and taking them out of sections, and finally arrived at something that I was happy with.

I think it was also difficult in a different way than the chapbooks were because the earliest poem in this book is one I wrote when I was in undergrad. The latest poem is one that I probably wrote two years ago, a year or two ago, I don't know. And so, there was, I think, about 10 years across the poems. I don't think a reader will be able to pick up on that. But it was hard for me to not be painfully aware of that as I was organizing the poems and choosing which ones to include and which ones to cut. It would just feel like there were these big gaps between the older poems and the newer poems. And if I put them beside each other, that felt wrong. And so, I sort of had to get over that.

JC: Which feelings would you choose to describe Red Ocher?

JP: Lonely. Hopeful. And startled.

JC: Why lonely?

JP: A lot of the poems directly address loneliness. A lot of the poems are about failed relationships. Feeling betrayed in some way. Feeling let down. I think the most work I put into this manuscript was during 2020. So, a lot of my work on it was done while I was quite literally alone. I was just sitting at home with my cat. Also, throughout that ten years when the poems were written, I had many periods of feeling lonely, even if I wasn't necessarily alone. And that is complicated, and I'll talk more about that with my therapist.

JC: Why did you choose startled?

JP: I picked that because I was thinking about poems like the ghazal, that poem “Floristry,” and a few more that sort of leapt onto the page and I didn't have to do much to them afterwards, because they came out fully formed. I think that’s because I had them sitting in me for some time. The emergence of them was startling.

JC: I think “Floristry,” “Greenbrier,” or “Afterimage” are some poems that come to mind when I hear you say you were startled.

JP: Afterimage was another one that startled me, but for a different reason. It startled me that I wrote about it so directly. Ten years ago, I might have written about it, but I would have veiled it completely behind metaphor and figurative language. It startled me that I just went for it.

JC: Why hopeful?

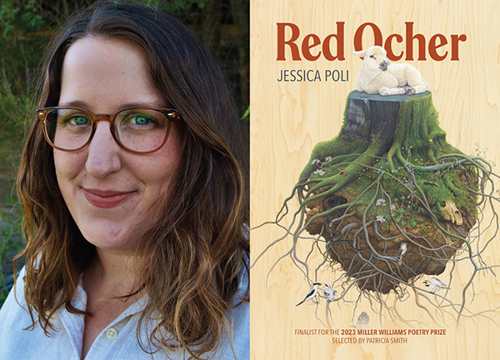

JP: I think, overall, the poems are hopeful. They talk about some sad things, but I think I, as a person, often lean towards hope. I think that's reflected in the poems. I almost went with a different cover art. The first artist ended up never getting back to us, which I think actually worked out really well, because that piece felt darker. It was a little more gloomy. It was a beautiful piece of art, but this one, I look at it, and I feel hopeful. If you read the artist statement by Tiffany Bozic this is actually a pretty dark piece as well, examining the human impact on various ecologies. But visually, it's also bright and beautiful and lush and green—and I find the contrast between the meaning and the form interesting.

JC: In my reading, some hopeful poems that are included in this collection include poems like “Gastronomy” or “Ode to Seventh Grade Girls.” Love comes through in shocking ways in those poems. There’s the love of one’s community. Love for the self. Love for healing and processing.

JP: I almost didn't put “Ode to Seventh Grade Girls” in the book because it felt like it didn't fit. But I ended up keeping it because it felt important for the reason that you're saying. I wanted to offer a different version of love, a different version of hope.

JC: Here's one last question: what's something that you're excited for? What’s coming up on the horizon for you?

JP: I'm reading a lot of amazing books right now. I have a stack of books a mile high that I brought back from AWP, and they're all so good. In my to-be-read pile next is Vievee Francis’s new book, Patricia Smith's new book, K. Iver’s new book.

Recent books that I've read are Margaret Ray’s Good Grief, the Ground, which just came out from BOA. That is the one book I've read since I got back from AWP. It was astonishing. It's so good. Otherwise, I’m looking forward to getting back to writing. My head has been very full of the business side of poetry, just trying to birth this book into the world. I'm grateful for that, and I'm excited to continue celebrating it and sharing it, but I'm also really excited for things to quiet down and to get back to just making the thing.

Jessica Poli is the author of Red Ocher (University of Arkansas Press), which was a finalist for the 2023 Miller Williams Prize. Her work has appeared in Best New Poets, North American Review, Poet Lore, and Salamander, among other places. She is currently a PhD student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Jordan Charlton is a poet and PhD student in English at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where he teaches in the Institute for Ethnic Studies and serves as associate nonfiction editor for Prairie Schooner. His writing has been published or is forthcoming in Atticus Review, The Adroit Journal, Quarter After Eight, Ruminate, The Journal, West Branch, and elsewhere. In addition to his academic pursuits, Charlton works with the Nebraska Writers Collective as a teaching artist facilitating workshops with both high school poets and incarcerated writers through the programs All Writes Reserved and Writers’ Block.