Sturge Town is an astonishing and intimate volume that vividly renders Kwame Dawes’s reflections on his ancestral home in Jamaica and what it means to carry the weight of a lifetime of memories. The poems offer a compassionate insight into history and identity, triumph and loss, joy and grief, and love and relationships. Dawes’s mastery, beyond his excellence at the craft, is his radical attention to and unwavering interrogation of the human existence—its inevitable tragedies and ordinary pleasures. Sturge Town is a deeply fierce and candid meditation on life and Dawes invites us into the anthem of his memory: to hold firm to beauty in the midst of chaos and to “make our own path from day to day, knowing that maybe faith is the buttress against the noise.” In this interview, he shares stories about growing up in Ghana and learning from his mother’s artistry, his thoughts on confessional poetry and the writing of elegies, and the experiences that have shaped his thinking and practice of the craft.

Tryphena Yeboah: When you showed me a photo of your house in Sturge Town, I was struck by its exterior—the rusted tin roof, the ashen walls, the missing louver blades, and the greyness of its condition, against the contrast of the bright green trees that towered over it. There’s almost an eerie feel to the house and perhaps the sense that its decay and ruin are precisely the evidence of the lives it sheltered, the stories it held, and the changes it endured. When you think of Sturge Town what are the first things that come to mind?

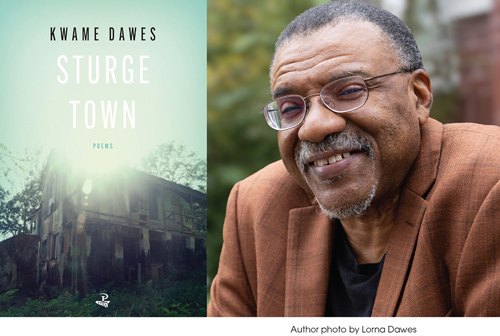

Kwame Dawes: Sturge Town is a village in the hills of St. Ann, a parish in Jamaica. It was my father’s childhood home, and the house there, which is in the picture that exists on the cover of the UK edition of the book, is where my father, my grandfather, grandmother, and my great grands lived in the 19th and early 20th centuries. When we moved to Jamaica, we lived in Kingston, and while we visited the village, we never lived there, and by then the house was no longer occupied by the Dawes family, even though, as far as I know, it was owned by my father and his siblings. But in terms of “ancestral” homes, Sturge Town holds a central place for me. Growing up in Ghana, Sturge Town came into our imagination as the symbolic site of everything Jamaican, and my father told us rich stories about the village, the rural existence, and much more. Sturge Town represented the “other” home for us—we being both Ghanaian and Jamaican, and Jamaica being our “other” home. Of course, over the years I have learned a great deal more about the village, about my ancestors, and about what it all means, and I hope much of this is what comes through in these poems. The house is currently in an exquisite state of disrepair, and there is a haunting reality in the lingering beauty of its seat on the hill, the riotous vegetation, and the “good bones” of its structure. But as you can tell, Sturge Town is both rooted in historical and familial reality and the poetic possibilities of myth and invention.

TY: Several poems in Sturge Town are in conversation with paintings and photographs by artists including Alfred Stieglitz, Mario Algaze, and John Singer Sargent. Do you remember your first experiences with art? How has your engagement with it changed over the years?

KD: My mother completed training as an artist in Ghana, and continued primarily as a sculptor for years, despite working as a social worker and doing other kinds of work. At the same time, she painted, drew, and did a great deal of batik painting and design work. Later in life, while living in Tortolla, she began to paint more and built a body of work as a painter, primarily acrylics and ink. Since she became blind several years ago, she has been unable to work.

As a child, I found myself serving as her apprentice especially as she sculpted. I would help her mix plaster of Paris, to prepare the clay for moulding, and so on. I learned a lot, and she pulled me into all her technical efforts. When she did her amazing batik painting, she gave me lessons on how to handle wax, all the equipment, and the improvisational and technically complex process of creating art in this medium. She taught me how to do lino-cut and print work, how to do block printing with potatoes, and much else. During those days, she would talk about great art from the world over—her tastes were eclectic. She had books of art that she would talk casually and informatively about, and I was happy to listen and learn. From an early age I liked to draw, and so I think it made sense that we would connect in that way—her encouraging me, and me happy to be around places where drawing and making art were the intended purpose for being there.

When we moved to Jamaica, my father was the director of the Institute of Jamaica, which was the cultural institution of the island. This ensured that we would find ourselves waiting around at art exhibitions and musical performances, attending major theatrical productions, and of course, watching the artistic minded entertain themselves. We were eavesdropping on all of this, but it certainly normalized the artistic pursuit in my mind. So I can’t say I know when I actually became interested in art, and as for the ekphrasis, one would have to connect that to my growth as a poet and seeking different ways to connect poetry with the artistic things that engaged me, whether music, dance, art or other literary pursuits. I found myself excited by art as a playwright—theatre being a form that draws on so many artistic skills by different people. And I don’t think any of that left me when I began to write poetry seriously. I consider my engagement with or “use” of art as part of my poetic practice—the ways in which I draw on the artistry of other artists in the world. And I have found that when I am in conversation with art—visual art—my poetry stays alert to the visual, the physical and the dynamic qualities of composition. I try to downplay the use of the term “ekphrasis” to describe these poems because I have to be honest, I am attempting not to be faithful to the art.

TY: In the poems “Before the Memory” and “The Child Learns of Death,” you capture the young awareness of death and endings, what is left unspoken in the interim between illness and death, and how this kind of knowing almost strips away one’s innocence. When my father was sick, I fed him and took him to the bathroom, while my brother helped lift him up on his feet. Reading these poems, I couldn’t help but think of the level of care and empathy you bring to these subjects and your treatment of these kinds of relationships where something significant shifts, and one isn’t quite the same afterwards.

KD: Thanks for what you say here. I don’t think we are ever prepared for what it means to face the death of a loved one, and especially the ways in which we encounter the death, whether through sickness, caring for them, or dealing with the aftermath of that loss. I think writing about these things can be problematic because we somehow can, and should, be the subject of such poems, even if we speak of the poems as if we are writing about those we have lost. So I prefer to consider these poems as elegies, elegies that, as Romeo Oriogun mentioned in a tweet, we are able to care for our ancestors. The elegy as an act of caring is generous and, at the same time, healthily selfish. Poetry, for me, is a way to think and feel deeply about these heightened experiences and in the “telling” to arrive at a better understanding of what has happened and where we are in the midst of these things. This is what poetry is for me as a maker of poetry. I suspect that I am drawn to poems that seem to, but their sincerity of sentiment, allow me a point of empathetic engagement, which is a wonderful imaginative exercise at the end of the day.

TY: I’m curious to hear your thoughts about the risk involved in art, particularly when writing about people in our lives. How do you find the balance in choosing what to share and how much to share? Does it help for one to consider the question, What is at stake?

KD: I like and appreciate the way you asked this question. In a sense, this is not a question about writing about the subject of what we write, as it were, but about what we share. And there is, and has always been, for me, a difference between what I write and what I share or publish or read publicly and everything that “publishing” means. And the considerations there, while artistic, have a great deal to do with what my life’s priorities are at a given time. I know writers for whom the matter of publishing is not complicated. The art is priority. I don’t share this view. I do believe that my life, my loved ones, my principles, and my engagement with the world at a given stage in my life, is what guides what I share/publish, and what I don’t. But I have disciplined myself to write about anything. Because writing for me, especially writing poetry, is a process of discovery and consideration—it is a way for me to come to some understanding or seeing of my thinking and my feeling and my engagement with the world, with art, with beauty, with spiritual matters, with everything.

Maybe a better way of thinking about this lies in how I approach writing. While I may be moved by or drawn to the page by a feeling, a sensation, or an image, almost always, I come to the page prompted by a desire to make a poem, to make art. It is a visceral sense, yes, but it may be driven by a compulsion to enjoy the sensation of making something called a poem that has consumed me and moved me. I am drawn to this, dependent on it in a way of finding ways to face the world. I would call it an “addiction” but that would trivialize more weighty and debilitating addictions; and I would not want to do that at all, ever. But like a delicious meal, and the sensation of it, or some other kind of desire, a sense of being loved, or amused to laughter—a body-emptying kind of laughter, or a haunting feeling of optimism in the world that can overtake my body, making poems can have that effect and that draw. So I want to repeat that sensation, and as it happens, the sensation has less to do with the subject of the poem than it has to do with the mechanics and the effect of making the poem. If we begin there, then you will know that my impulse to not limit my subject of anxieties about someone reading what I write, don’t figure much into what I do. I am acutely aware that I can discard what I have written. I think, though, there is a more important lesson I have learned over the years. Poetry has a way of reshaping what I have imagined to be the known thing—the story, if you will. If a subject and its disclosure exist in my imagination as tabu, I have come to mistrust that imagined anxiety, until the poem engages this thing and shows me that it is tabu, or worth putting aside. Our human interactions are as much defined by the facts of our actions and the ways in which we receive, recall and respond to them. And poetry finds a path to our understanding that makes truth, sometimes, the healing beauty. Not always, but sometimes. And it is worth finding out.

Finally, when the matter of sharing comes about, I can edit for that purpose. I have edited, changed details, disguised, and masked historical details, while retaining what I like to think of as the emotional truth of the experience and the idea. I have no problem with this, at all. And families of writers always suspect that despite what emerges on the page, they are dealing with people who mine their lives for material. I will always prioritize protecting those I love and value over having a work “succeed” in the world.

TY: My favorite poems are the ones about fathers—you as a father and your relationship with your father, Neville—“It Begins with Silence”; “Fish, Serpent, Eggs, Scorpion”; and “What a Father Gives,” a poem that moved me deeply for its familiar voice, its honesty and emotional risk, and its clear articulation of what, at least for me, remains unchartered territory. I would love to know your thoughts on honesty and courage in writing, and how being a father informs what you put on the page.

KD: It is interesting to me that with some effort, my poems will reflect various aspects of my existence—the obvious matters of my biography, and the less obvious matter of my thoughts, fears, dreams, and fantasies; and finally, my intellectual and emotional core—what moves me as a human being encountering the world. I do write about elements of fatherhood, but I can’t say that this is something that dominates my work over other things. But poetry helps me to engage the various parts of my existence, and this is the exciting thing. I do appreciate what you say about “honesty” in poetry. I do know that honesty is a slippery thing. It is like memory which is, itself, quite slippery, even as it is thick with feeling and even as it defines how we engage the world. What I will say, though, is that even though such honesty is deemed as courageous, in my experience, the freedom (for that is what it is) to be honest is less so a product of courage and more so a gift of protection. I have envied those who live with complete openness, without secrets. In many ways, they disarm the weapon of exposure that can haunt our lives all the time. I also have come to trust that sincerity of sentiment makes for poetry that achieves something beautiful and lasting. It is certainly not everything, but it is there. And this sincerity comes from resisting the urge to make ourselves the noble heroes and heroines of all that we write when most of the time we are not. The temptation is great. I used to say that as a writer I have this power of turning even the most humiliating of accounts into celebrations of myself. But I do think the poet who is sincere will at least show that all truth is nuanced and a navigation between desire and experience.

TY: We see the body take on many forms in this collection, and I am particularly curious about your intimate and confessional voice about the rituals of living and loving, loss and the perpetual weight of grief, and aging and dying—all of which are housed, and sometimes hidden, within one’s body. This inward gaze, and the sort of openness to whatever end lies in wait…how did it come about? Or, I suppose, what I’m really wondering is how does grappling with the failings of your body, your own death, make you think differently about living and the poems you write?

KD: I said earlier that one of my poems is a confession to my son about my failure. I used the word “confession” in the most limited ways that I feel comfortable about in terms of its use in poetry. I don’t regard my poems as “confessional” in the way the term is used in literary history. The confessional poem is an inadequate metaphorical description of poetry that seems to reveal much about the poet. By my count, poetry has been doing this forever—as far as forever can go. There is nothing that happened in the 1950s in America, that changed that. So when I am writing about my body, I am writing about what is available to me. I limp a lot because I have a pain in my ankle that got there after a car accident when I was seven years old. The healing was just not great after the break. That is my body. My eyes are what they are, and so I am concerned about sight. That is my body. I am overweight and I have been aware of my weight for a very long time, sometimes delusionally, sometimes practically. And I am a black man, and it has implications for how I move in the world. I also am aware, perhaps as a product of age (though I think I have always had this morbid intimacy with the idea of aging and death), of my mortality and the ways in which death is a peculiarly dogged inevitability. And this body has given me pleasure, has carried me into so many places, has delighted me, and has betrayed me. And I have betrayed this body, too. The embodiment of poetry is a thought for me that holds water. I think I have been “fearfully and wonderfully made,” and so writing about this machine strikes me as a thing that I should not ignore. I don’t know if any of this makes me think differently about poetry—no different from how it may have affected my poetry earlier in life. I am not saying anything profoundly new here. I wish I could remember which famous poet said that all poetry is ultimately about death. I am sure their friends took this statement more seriously when the poet eventually died. Another poet, probably French, said every poem is a little death. They died, too, and here we are, keeping them alive.

TY: Are there writers you find yourself returning to over and over again?

KD: Yes, there are poets I return to. But this is the question I don’t like to answer; I think I always do my list a disservice because I do not have an existing list. I return to poets when a particular problem I am dealing with makes me think of them and want to see how they solved it in poetry. I also return to poets when I want to test what I think of the quality of my poems. I test my growth as a poet, and the quality of each poem against the poets I have most admired or the poems I have most admired. And by admired, I mean they have challenged me, impressed me, left me thinking, “how stunning!” or “how true!” or “how beautiful!” I guess the host of poetic witnesses that hover around me are the ones that keep me honest. But most recently, I think two experiences have stayed with me. The first is the weeks I spent listening to the complete poems of Seamus Heaney on a magnificent audiobook series. The chance to travel with Heaney through his entire career as a poet, and to do so listening to him read these poems left me being so, so grateful for technology, for the cell phone and apps that allow me to walk through my neighborhood listening to the intimate sound of a major poet speaking his verse in my ears.

The second experience is listening to and reading Dionne Brand’s collected poems, Nomenclature, which was published in Canada last year. Wow! Again, listening to the poet speaking her poems in my head—that intimacy—feels like a gift. These are two masterful poets, yes, but listening to the full range of their work—at least, this curation of the work over time—is a revelation that is hard to deny. Brand chooses not to include some of her earliest work, but what is included is truly ranging and stunning. The orality of poetry is sometimes forgotten by many, and these two productions are good reminders of how much sound, spoken sound, is at the heart of poetic achievement. We need more poetry books on audio. We really do. I know that the publishers of such recordings are skittish about doing this with poetry, but I am committed to finding ways to ensure that my work is recorded and published.

Kwame Dawes is the author of twenty-five books of poetry and other books of fiction, criticism, and essays. His most recent collection, Sturge Town (Peepal Tree Press, UK 2023), is a 2023 Poetry Book Society Winter Choice and will appear in the USA with Norton in June 2024. Dawes is a George W. Holmes University Professor of English and Glenna Luschei Editor of Prairie Schooner. He teaches in the Pacific MFA Program and is the Series Editor of the African Poetry Book Series, Director of the African Poetry Book Fund, and Artistic Director of the Calabash International Literary Festival. Dawes is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, the winner of the prestigious Windham/Campbell Award for Poetry, and was a finalist for the 2022 Neustadt International Prize for Literature. In 2022, Dawes was awarded the Order of Distinction Commander class by the Government of Jamaica.

Tryphena Yeboah is a Ghanaian writer and the author of the poetry chapbook, A Mouthful of Home (Akashic Books, 2020). Her fiction and essays have appeared in Narrative Magazine, Commonwealth Writers, and Lit Hub, among others. She is a PhD student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.