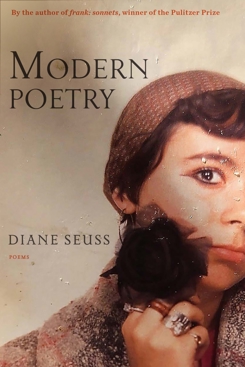

Graywolf Press (March 5, 2024)

Last year, several of my undergraduates were swooning with crushes on John Keats. Yes, John Keats, the Romantic poet, tubercular, and so short, Diane Seuss writes of him in Modern Poetry, her divinely cobbled sixth collection, “[t]he top of his head would have barely/reached [her] tits.” Many of Seuss’s poems refer to Keats, and my students’ stories starred Keats as protagonist, stories so sacred they didn’t want me to critique them. “Look,” one said, pulling up a sepia-aged sketch on a Google image search. “Just look at him.”

I looked. There the poet was, drawn by his friend Joseph Severn, and looking every bit the sort of romantic to stare longingly into a distance as he contemplates truth and beauty. I looked, and, as Seuss’s speaker writes in an earlier poem from frank: sonnets, “I lied that I could see the beauty there.”

“I barely remember what it was like to have intense crushes like that,” I said, and the class looked at me in a generation-gap horror. But perhaps I have not completely lost my capacity for fervent devotion, since I find it difficult to write critically about Seuss, whose collection is haunted by the ghost of that feverish Keats. I will endeavor, at least, not entirely to rhapsodize.

Many of Modern Poetry’s jauntily rhythmic or rhythmically woeful poems skip with internal rhymes and take poetry back to song—many of these are ballads, jukes, pop songs, and folk songs. One finds oneself in a wood; it is cold there, and it is winter, but the sounds seduce, as in “Little Song”: “heedless/in your posh knee socks, your ritzy lamb, your/lush pop beads, your lilac jam, your breathless, / deathless, feckless little song.” One desires to rid oneself of complexity, the heft of a lived life: “Memory a tree so loaded with fruit and birds the tips / of the branches rake the ground” (“Folk Song”). One longs for a place, like “the north,” where “all forms stood for themselves. / There was no need to fill them with anything” (“Allegory”). One wants to dump over-used words and overdetermined metaphors, preferring jukeboxes with only three songs, and mouths with only three teeth. In “Coda,” the speaker claims that “[t]he best poem is no poem.”

But no. “I’m copious, and so are you,” is repeated in “Cowpunk,” and these poems are “the rhapsody of things as they are” promised by Wallace Stevens in an epigraph. In “Rhapsody,” Seuss writes,

...Some poet wrote

that he adores economy and requires precision.

I actually looked for antonyms:

extravagance, ignorance, imprudence, negligence, squandering.

I felt like a poor kid who finds a quarter and gorges

themselves on penny candy. From then on, everything

I created or promoted would be rococo.

Modern Poetry offers us the world as plainly and as copiously as it can, and the best poems in it, if a broken romantic may make a bold assertion from her weedy desert, are the ones about poetry. The collection offers a poetic education, dedicated to “my Reader,” which this particular reader—who walks around over-educatedly but very innocently asking how she can know whether a poem is any good—got when she needed it.

In “High Romance,” very near the end of the collection, Keats’s ghost loses his grip on concepts and meaning: “Words, he now knew—and he’d once been / such a devotee—didn’t matter.” Poetry must be useless. Diffuse. Must exist on its own behalf. And what is beautiful is not the object but the gaze—that’s the beauty / truth thing: “His gaze / was too objective to find her beautiful, / but objectivity itself—that was beautiful.” It is high romance to turn away from romance. In Modern Poetry, the word “love” is not enough for those who love.

Since so many of Seuss’s lines are concerned with questions of cynicism and romanticism, it is appropriate that I spent Valentine’s Day floating in them. I was like the poems from an anthology of modern poetry the speaker in “Romantic Poetry” imagines sliding from the book’s spine into the sewer:

down where my uterine lining, my blood

and cast-off ovulations, cast-off fetal

tissue swims, below the city.

The microdead ride modern poems

like swan boats in the park.

Diane Seuss is the author of six books of poetry, including Modern Poetry; frank: sonnets, winner of the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and the PEN/Voelcker Prize; Still Life With Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize; and Four-Legged Girl, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She was a 2020 Guggenheim Fellow, and in 2021 she received the John Updike Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Seuss lives in Michigan.

Liz Harmer is a Canadian living in California and the author of the novels The Amateurs (2018) and Strange Loops (2023). Her award-winning stories, essays, and poems have been published at the CRAFT, the Globe & Mail, The Walrus, Best Canadian Stories, The New Quarterly, Hazlitt, Image Journal, and elsewhere.