August 2022

Natural Dyes in Harmonist Times

Peggy Taylor, Heritage Artisan and New Harmony Resident

The Harmonists created, adapted and adopted the new technologies of their day giving them a competitive edge in the growing early American economy, particularly in textile manufacturing—wool, cotton and silk—and agricultural production. By 1825 they had constructed textile factories powered and heated by steam engines. They built shops for blacksmiths, tanners, hatters, wagon makers, cabinetmakers and wood-turners, linen weavers, potters and tin smiths, as well as developing a centralized steam laundry and a centralized dairy for the community. Later, they perfected the technology of silk manufacturing, from worm to fabric, for which they received gold medals during exhibition competitions in Boston, New York and Philadelphia.

Gertrude Rapp (1808-1889) was the granddaughter of George Rapp, founder and leader of the Harmony Society. Gertrude was a member of the Harmony Society and a pioneer in the American silk industry as foreperson of the Silk Mill at Economy, Pennsylvania. Miss Rapp supervised the production of silk goods equal or superior to those imported from Europe.

Dyes available to the Harmonists were plants from the area: walnut hulls for brown, a variety of yellows and golds from dyers chamomile, marigold, tansy and coreopsis; rust and gold from onion skins or from the wood of the Osage orange tree; red and orange from madder root. Other dyes commonly used during the early 19th century here in Indiana and at Kentucky’s Shaker Village were imported from more tropical climates: indigo from fermented indigo plants for blue, woad leaves also for blue, cochineal from shells of the cochineal beetle for reds, logwood and brazilwood for reds and purples, and fustic for strong yellows.

To weave their woolen, cotton and silk fabrics, the threads would have first been spun and then dyed. Mordants (chemical substances like alum, cream of tartar, vinegar, tin, iron and copperas) were used to prepare the threads to take the dyes. New Harmony’s location on the banks of the Wabash River was ideal for both the dyeing process and for the mills that would have produced the cloth of excellent quality that the Harmonists produced, used and sold.

The dye process involved soaking the dye material (for example, marigold flowers or crushed walnut hulls) in water, heating it to simmer while the color is extracted, then straining the dye liquid. After this the wet wool, linen, cotton or silk yarns, tied loosely in skeins, were immersed in the dye liquid and gently heated. When the desired color of yarn was achieved, the skeins were removed, rinsed and allowed to air dry. For Harmonist looms, a very great quantity of dyed yarns would have been required—a mill could use up several hundred pounds of yarn for a month’s worth of weaving.

If this process piques your interest, Historic New Harmony is offering a Natural Dye workshop on Saturday, September 10, at the cabins on West Street. An outdoor dye station will be used, and several plants grown in the nearby David Lenz house dye garden will be prepared and used to dye sample skeins of wool yarn. Each participant will get to dye four skeins of yarn to take home, with a resource sheet about the natural dye process, and a list of the Lenz house dye plants that are being cultivated here. You are invited to learn more about the fascinating world of plant dyes as used by the Harmonists, dyes that are still important to today’s weavers and fiber artists. Nature provides a wide array of color to brighten our lives if we just know where to look; come and try natural dyeing for yourself—and feel a kinship with nature and with the Harmonists who lived here before us.

The Harmonist Brick Church and the “Door of Promise”

Claire Eagle, Interim Assistant Director

There is no clear reason why the Harmonists decided to build a second church. The first church, a white wooden framed building, was built only a few years earlier in 1815. Three stories tall with a steeple and bell, this building was exactly what you picture when you hear the word “church.”

The Harmonist Brick Church was much different. Built in the shape of a Maltese cross, each arm was equal length and had an entrance. Travelers were often amazed at the beauty of the architecture and would document what they saw. William Hebert in his writings stated, “I could scarcely imagine myself to be in the woods of Indiana, on the borders of the Wabash, while pacing the long resounding aisles, and surveying the stately colonnades of this church.”

The north wing had the “Door of Promise.” Designed by Fredrick Rapp, the lintel featured a carving of the golden rose, the year 1822 and the inscription of Micah 4:8. This verse from the Bible, translated by Martin Luther reads, “And Thou, o Tower of Eder, a stronghold of the Daughter of Zion, Thy Golden Rose shall come, the former dominion, the Kingdom of the Daughter of Jerusalem.” The golden rose used in Luther's translation is an allusion to a symbol given to kings who were favored by the Church. The rose also represents the restoration of God's kingdom on Earth, which is centered at Jerusalem. The rose became a trademark of the Harmonists’ exports as they were anticipating the second coming of Christ and the restoration of God’s kingdom on Earth.

Years later when a delegation of Harmonists led by Jonathan Lenz and Jacob Henrici returned to tear down the Church , the bricks were used to build a wall around the Harmonist Cemetery, which still stands today. However, the “Door of Promise” remained and became the north door to the New Harmony School. When that school was torn down in 1913, the door still stood and became the west door of the new school. The 1913 school was taken down in the fall of 1988 and the “Door of Promise” was finally moved from where it stood for over 100 years. The doorway, lintel and remaining windows were moved to a storage area for safekeeping. These items are now in the Historic New Harmony collection, and we hope to exhibit them soon.

Christmas Traditions

Paul Goodman, Experience Coordinator

Christmas during the nineteenth century here in New Harmony wasn’t celebrated the same way we do today. The Harmonists had no lights, no inflatable snowmen or Santas and no celebration of the nativity. There was more religious zeal than all the glam and glitter. However, some Harmonists would have some simple decorations in their homes. Christmas day would have been heralded in with laurel, myrtle, orange branches and ivy draped across mantels and lintels. Simple swags of holly, ivy and other branches would be placed on fence gates and sills. Being from Germany, they did practice the tradition of the Evergreen tree, but instead of baubles and string lights it would be trimmed with cookies, colored popcorn, nuts and oranges. At noon, the children of the community would receive a sack with a combination of candy, colored popcorn, an orange, walnuts, dried grapes, figs and dates. In the evening, there would have been a large feast of rice soup, roast veal, beef, apple schnitzel, sauerkraut, bread, ginger cakes and wine. No talking was allowed during the feast except for the music that was to be played and sung between the courses. However, this was not a day that they would’ve gotten off from work like we do today. Work would’ve continued throughout the festivities, as well as three church services throughout the day.

The Owen community, as well as many around the rest of the United States, continued to celebrate Christmas depending on where you came from and what your country-of-origin traditions were. Many in the Owen Community that came from Britain would feast, gamble, hunt and visit with friends as such as the customs in British manors would be. The feasts would be grand with goose being the main star of the meal. If you could not afford goose, many people celebrated with rabbit. If those with wealth wanted to be like Queen Victoria, they would have a lavish feast with beef and a royal roast swan or two. If you came from France, you would put up your crèche, or what we know as the Nativity scene. Then, the children would put their shoes by the fireplace to be filled with gifts from Pere Noel and the adults would feast during Le Réveillon, which is an after midnight large feast. Food was a main component in French celebrations at Christmas. One dish that was served during this feast you might recognize is la bûche de Noël, or the Christmas Log. If you were of the Puritan religion, you did not celebrate Christmas because the Bible does not mention it.

As time went on, new conditions in America began to undercut the local customs to make way for the common celebrations we know today. Advances in communication and transportation made it possible for all of these different traditions to mix. Immigration to different parts of the country, new wealth and larger markets superseded old ones, population boomed and the pace of everyone’s lives accelerated. The thought of a family joining together around a fireplace bringing the past and the future together made the country very nostalgic. Christmas began to resolve into a more singular and widely celebrated holiday for families at home. It gave families time away from all the craziness of contemporary life to remember their heritage and to celebrate it with their family. The Civil War intensified the Christmas appeal. The sentimental celebration of family matched the yearning of soldiers and those whose lives had been lost. Its message of peace and goodwill spoke to most of the American families praying for their loved ones.

After the war, the symbols of the modern Christmas began to take shape. The German Christmas tree became an icon as more and more people saw them in German American homes and through media, such as newspapers. By 1900, one in five Americans were estimated to have a Christmas tree in their homes. The act of giving gifts at Christmas started to increase as well. More Americans were giving gifts as a symbolic solution to the problems with economic inequality that was growing in America in the late 1800s. However, this became very controversial because some felt that it was a materialistic perversion of the holy day. Most people chose handmade gifts over the commercial ones from factories or stores. To help them sell more gifts some of the larger stores started to wrap their gifts in bright colors and tinsel to mask the fact it was manufactured rather than homemade. This also allowed for a moment of revelation when the receiver would open it. Through the works of newspapers and illustrations, Santa Claus would become the figurehead of the American Christmas. Christmas in America has changed even more so than in the 19th Century, but the values of family, love, unity, peace, heritage and goodwill will live on for centuries to come.

Pioneer Hearth Cooking Demonstration

Join Historic New Harmony Interpreter Becky Smyth as she demonstrates pioneer hearth cooking. Ms. Becky has been an interpreter at HNH for over 30 years, guiding tours, demonstrating Harmonist cooking and candle dipping and so much more!

Historic Candle Dipping Demonstration

Join Historic New Harmony Interpreter Becky Smyth as she demonstrates how the Harmonists made candles during the early 1800's. Ms. Becky has been an interpreter at HNH for over 30 years, guiding tours, demonstrating Harmonist cooking and candle dipping and so much more!

Robert Owen’s Economic Experiment at New Harmony

Rod Clark, Historic New Harmony Advisory Board Member, New Harmony resident and local business leader

Of the many reasons we celebrate the life and legacy of Robert Owen, perhaps the least talked about, is the practical and pragmatic application of his socialist economic ideas at New Harmony. Simply put, Owen’s experiment at New Harmony was the world’s first attempt at secular socialism. Religious groups such as the Harmonists, the Shakers and others had devoted themselves to communities of shared ownership in property, but Owen’s New Harmony was something different. It was not led by a religious autocrat who suggested that the communal lifestyle was a dictate by God (e.g., George Rapp and the Harmonists), but instead led by a man fully detached from religious fervor. Robert Owen was instead motivated by the ideas of a new world order that was strictly secular and motivated by earthly aspirations, not heavenly.

Owen’s background as a successful industrialist in New Lanark, Scotland was a direct testament to the profound economic changes brought by the industrial revolution in Great Britain. The change from a feudal agriculturally based economy to mass production created by machinery, led to vast economic disparities that Owen saw firsthand. While he benefited directly from this new system, he found its economic consequences to the working class too burdensome. He came to believe that the chasm of economic benefit between the owners and the laborers brought on by industrial revolution could be overcome by a new system, a new world order.

Adam Smith’s ideas of laissez-faire capitalism would be replaced by “villages of cooperation,” where free-will men and women (as opposed to religious directive) would share and share alike. Owen suggested that human nature would lead to a communal “terrestrial paradise” of shared economic toil and gain: secular socialism.

Owen’s economic experiment at New Harmony was an unmitigated disaster. Why didn’t it work? There are many reasons. Most notably, the idea that intellectuals, laborers, academics, artists, educators and common factory workers were all supposed to share and share alike in a mutually equal manner was simply too big of a secular leap for most to make. “Surely you don’t mean that my educated intellectual background has the same value as this person who showed up in our community in order to share in the gains!” was a common cry that couldn't be intellectually substituted with high mindedness or great ideas. Socialism turned out to be as messy as laissez-fair capitalism. The devil was in the details, and unfortunately Robert Owen was too infrequently in New Harmony to lead his followers through the details of his new system.

Regardless, Owen’s experiment was important. No one had ever tried it before. Economic historians will note France’s Henri de Saint-Simon’s (1760-1825) ideas of how a “brotherhood of man” should direct the economic mechanisms of the state. But Saint-Simon’s ideas were simply that: ideas. Owen took his ideas and put them into practical application (or at least tried to) in New Harmony. The experiment allowed others to evaluate and analyze the reasons for that failure.

Twenty to twenty-five years later, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels labeled Robert Owen as a “Utopian Socialist.” Engels in particular wrote extensively and approvingly about Owen’s socialist ideas. (Engels contributed to Owen’s periodical New World Order.) Both Marx and Engels agreed that Robert Owen’s system was right and just. What they disagreed with was his idea of wrapping it within a system of kindliness and secular charity. While they drew inspiration from Owen’s New Harmony experiment, they came to believe socialism (that they would call communism) could only really be achieved via the bloody-mindedness of the French Revolution, the thrill of violence and class struggle.

There are many reasons to celebrate and commemorate the 250th anniversary of Robert Owen’s birth. More celebrated minds of the Western intellectual traditions such as Thomas Locke, Bernard Mandeville, David Hume , and Adam Smith have captured most of the academic and intellectual discussion on how we came to be the way we are today, but these individuals and others remained in the realm of intellectual thought and not practical application of their ideas in the real world. That was Robert Owen’s great contribution to economic history. His New Harmony experiment was the first secular attempt to explore an economic system that is still being talked about today. Those doing the talking have the New Harmony experience to learn from. We can thank Robert Owen and his New Harmony experiment for that.

Mr. Clark is a guest writer. Please note that any opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the University of Southern Indiana or Historic New Harmony.

Robert Owen's Life and Legacy

Claire Eagle, Community Engagement Manager

Within the society, Owen thought it could be best to approach improvements in two steps rather than one giant leap. He began by introducing a constitution that had set rules involving membership and ownership that everyone had to sign. A constitution for the “Preliminary Society,” intended to last three years, was adopted in May 1826. Equality was prioritized to make the community more of a large family rather than levels of power. While the constitution contained great ideas, it was vague, and the society was not built to last. Owen quickly left New Harmony to settle his affairs in Scotland, while Maclure worked to attract educators and scholars to the community in hopes of enacting his own social reforms and starting a labor school.

Upon Owen’s return, the community was facing growing difficulties. The population was larger than expected; accommodations and food supplies were scarce and only 137 members were a part of the "employed professions." Blind to the problems, Owen announced that the "Preliminary Society" had made progress and it was now time to enact the second step, the "Community of Equality." A new constitution was adopted with more lofty ideals, but no practical plans for organizing labor and distributing resources.

Economic troubles compounded when Fredrick Rapp arrived to collect another installment of the money due to the Harmonists. Maclure paid the money, then immediately filed a lawsuit against Owen for the same amount. An out of court agreement was eventually reached with Owen deeding 490 acres, half the town of New Harmony, to Maclure. In a March 1827 issue of The New Harmony Gazette, two of Robert Owen's sons admitted that the community had failed. Owen gave a farewell address and departed the community on June 1, 1827.

Robert Owen left New Harmony, leaving behind 80% of his fortune he had invested into the community. Owen had plans for other communities in Texas and Mexico, but nothing came of them. He eventually returned to Europe where he continued to fight for equal labor rights. Owen died in his birthplace of Newtown, Wales in 1858.

While the community in New Harmony was short-lived and, for all intents and purposes, a failure, members of the community, including his children, made extensive contributions to the fields of science and education. Furthermore, Owen's legacy is not only seen through his children and their families who remained in Indiana, but in the social reforms for which he advocated.

Owen had a major role in bringing change to labor laws with children. Both in New Lanark and New Harmony, children under 10 years old were no longer allowed to work but would instead attend infant school, which were similar to elementary schools today. Owen opened his first infant school and nursery in New Lanark, continuing the idea in his time at New Harmony. Owen also strived to limit the hours worked by children 18 or younger to prevent them being overworked and enabled them to obtain an education. Working with Maclure, the two were able to provide a higher education to children of New Harmony, specifically with scientific research. Finally, Owen’s children continued to push for many of the reforms Robert Owen believed in, including abolition, women's rights and education.

Join us this year, as we celebrate the 250th anniversary of Robert Owen’s birth with 250 days of programs, events, exhibits and more dedicated to sharing his life and legacy. Stay tuned in March for more information!

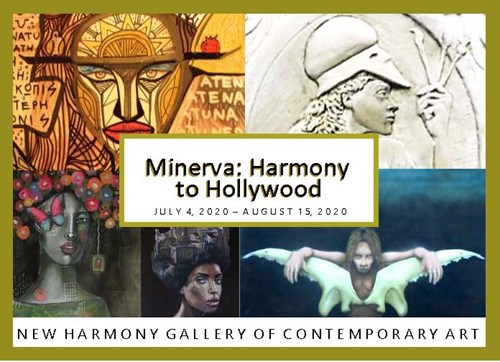

Minerva: Harmony to Hollywood

Jenn Horn, USI Instructor in English and Director of College of Liberal Arts Living Learning Community

In my Classical Mythology class, we love discussing the story of Minerva’s birth. Minerva, the daughter of Metis (wisdom itself), was born from Jupiter’s head after he swallows Metis to prevent their child from taking his throne. When Minerva is “born,” she is wearing her full battle armor and screaming a war cry! Minerva is not only the embodiment of wisdom, thanks to her mother but also a goddess “born from man” so she takes care of things that would normally have been left to men (commerce, wisdom in war, etc.). Minerva was unique in her attributes and stories of her were never associated with the emotional outbursts or “love” stories typical of other goddesses. It’s clear why Constance Owen Fauntleroy chose to call her woman’s literary club “The Minerva Society” after a goddess of calming strength and wisdom.

When approached to juror the New Harmony Gallery of Contemporary Art’s Minerva: Harmony to Hollywood exhibit, I was sure that someone had a made a mistake; surely, they needed an actual artist rather than just a lover of art and art galleries. The Gallery assured me I was qualified and so I agreed to go on this adventure.

One of my favorite things about this exhibit was the variety of ways artists represented Minerva and all her attributes. Minerva’s art and craftwork are well-represented in beautiful variety. And importantly, Minerva’s “wisdom in war” attribute, rather than the violence of war, is represented as are all the ways and places we use and need wisdom. Of course, all pieces found a way to represent the strong female body and/or spirit – a nod of respect not only to Minerva herself but to the participants of The Minerva Society.

To be honest, I thought the selection process would be easy, but this was much more challenging than I expected. It was an enjoyable challenge to be sure, but it was difficult to choose only 30 or so pieces from the many wonderful submissions. When I walk through an art gallery, I am amazed and impressed by the talent and creativity of the works on display; this exhibit is no exception.

As a skater and board member with Evansville’s Demolition City Roller Derby and a scholar of gender studies (the field itself as well as gender’s place in folklore and composition), I’d like to think I recognize a variety of aspects of female strength – the physical moments, the quiet moments, the self-reflective moments, the joyous moments and all the moments in between. It was truly an honor to be asked to participate in this adventure and I’m grateful to Tonya Lance for her guidance and patience during the process. And I am ever so grateful for every artist’s submission – thank you for sharing your talent and your vision.

Crowd Sourcing History

Claire Eagle, Community Engagement Manager

Those of you who are our fans on Facebook might have seen a recent post regarding this picture. A few weeks ago I came across this picture from 1900, in the Don Blair Collection in the University of Southern Indiana’s Archives and Special Collections, identified as the Cooper Shop with this caption: “Cooper shop employees and wares in New Harmony, Indiana.” As a part of our continued efforts to engage our community and visitors while closed, we have been working on a series of then and now posts of New Harmony businesses. For this post, we wanted to feature Black Lodge Coffee Roasters and the building they call home— the Cooper Shop. After finding this photo and determining that it looked quite like the current building, I went to our interpreter's manual to look up the information needed for the post.

But wait… the information in the manual did not match the photo label. The manual stated, with no source listed, that the Cooper Shop we know as Black Lodge was the second cooper shop the Harmonists built in 1819 and was moved to its current location in 1975. Additionally, this building had been used as a residence from 1893 to 1975. Before that, the building had been situated at the back of its current location and attached to the Union Hotel. I believe this is just a typo and they meant Union Hall, the name of Thrall’s Opera House from 1856-1888.

Somewhere, somehow, the information had been shared incorrectly, and I had so many questions. Was the photo of the first or second cooper shop? With no source listed, did we even have the correct information in our manual? I started by reaching out to Christine Crews, our amazing Administrative Associate who has an unrivaled institutional knowledge of Historic New Harmony. She had never seen the picture and wasn’t sure, so I was on to the next. I then reached out to Jennifer Greene, the University of Southern Indiana’s archivist, and all she knew was what was in the label of the photo. At this point, I knew our wonderful long-time interpreters could be the only ones with the answers. I emailed Linda Warrum, who reached out to others, and they were stumped too!

The mystery was growing, and I was now more determined than ever to find the answer. Which brings me to posting the mystery on our Facebook. I hoped that someone had information that could help us! We’ve had people offer their knowledge of the dress the men pictured are wearing to try to confirm the year the photo was taken, we’ve had others research at the Working Men’s Institute, but still no answer. If anything, the mystery has increased with each new piece of information.

However, we will not give up! Now I ask all of you to help as well. Have you read books on New Harmony that mentioned the Cooper Shop? Did you have family who might have worked there as a cooper? Or owned a business that called this building home? Let us know what you know by emailing me at ceagle@usi.edu. Help us solve the mystery!