A Witness in the Mist: Jacques J. Rancourt’s Brocken Spectre

by Amie Whittemore

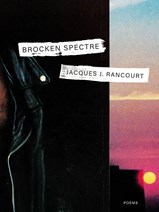

Reviewed: Brocken Spectre (Alice James Books, 2021).

Jacques J. Rancourt’s Brocken Spectre is part elegy, part ode—and it is also the synergetic place where these forms overlap, which has a name I don’t know (“odegy”? “elede”?) but is a cousin to nostalgia. These poems, in their examination of the lives of gay men during and after the AIDS epidemic, mourn the horrors of the epidemic of the 1980s and 90s while also carrying a wistful longing for community that coalesced in response to this crisis. As noted in “Western Wall,”

I don’t go to gay bars anymore

someone tells me & sure enough

another boards up soon there won’t be

a need for places like these

any more there’s a word for what we lose

when we gain our utopias

Thus, in some ways, the “brocken spectre” of these poems—the shadow in the mist as the epigraph from The Met Office notes—is the liberated gay man: free to marry, to fuck, to love openly (for the most part, in most places, in the United States) is a lonely figure: having gained so much of what heteronormative culture withheld—marriage, medical treatment—he has also had to pay a steep price. In “The Wake,” for instance, the speaker notes “that six hundred thirty-six. / thousand of us died & I did not. / know a single one.” This distance from the terror and grief of the AIDS crisis creates a kind of dissonance: the speaker neither being among nor knowing any of them can only be witness (or voyeur, depending on the angle of the gaze), as in the poem, “Kirby”:

I can nearly see

his body failing

his spirt

in equal measures

growing larger

as only someone

who did not live

through this

could possibly see

Bound up with this act of watching is a sense of gratitude and love—the speaker in “Voyeur,” for instance, observes older gay men at a bathhouse—“they laugh / silently & touch each other”—while “for a long time, from behind / the grill’s steel grate, I watch them.” The speaker’s gaze in this poem and others then is not so much a violating one as a way of offering tribute—acknowledging that there are distances he cannot cross even as he shares so much with the prior generations of gay men.

The distances in Brocken Spectre also include other grief, other (dis)connections: a cousin’s death by suicide, a war-haunted grandfather, the distances—or perhaps, more accurately, the complicated proximities—within a close, intimate relationship. While there is much to admire in this collection—its deft attention to the line, for instance, its gentle yet confident diction—what I find myself most drawn to are these proximities, these moments where the speaker must grapple with the challenges of intimacy. In “Where to Begin?” the speaker is flirting with another, presumably married, man, having “made no promises / to monogamy, but what to do / with those who have.” In “Jacques, from Jacob, renamed Israel, which means, in Hebrew, He Who Wrestles God” the speaker is “in the fourth month of our long-distance // the morning after I had slept / with somebody else.” What I admire about these moments is not only how they question monogamy, refuting the idea that monogamy is synonym to loyalty, but also how they refuse to justify or explain themselves: we are not let in on the details of these interludes. Instead, we are positioned as the voyeurs, the problematic witnesses to them instead—and who are we to make sense of other people’s loving?

And who is the speaker to do so? I think that is what these heart-rending, beautiful poems are most curious about: as both personal and collective traumas are examined, held up to the light, yet seen perpetually through a mist, it is not so much clarity that is manifested but wonderment: it is a wonder, though sometimes terrible, that we are what we are, that we do what we do. That we see what we see.

Amie Whittemore is the author of the poetry collection Glass Harvest (Autumn House Press). Her poems have won multiple awards, including a Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Prize, and her poems and prose have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Nashville Review, Smartish Pace, Pleiades, and elsewhere. She teaches English at Middle Tennessee State University.