The Meter Reader: Analicia Sotelo's Virgin is "cheeky and tender, endearing but with teeth"

Amie Whittemore

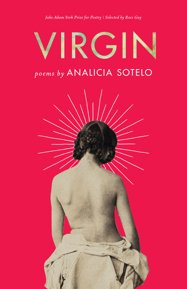

Reviewed: Virgin by Analicia Sotelo (Milkweed Editions, 2018).

There’s a special kind of pleasure that occurs when a “first” and a “best” coincide; a first-best taste of chai ice cream; a best-first date; rarely, though, is losing one’s virginity a first that’s also best. Still, I’m jealous of everyone who gets to read Virgin by Analicia Sotelo for the first time because this book is part-fire, part-labyrinth, part yolk spilling from its cage.

Broken into seven short sections, each building out of themes that occur in the preceding ones, the book is a delicious labyrinth. I relished following the thread of Sotelo’s thinking, her witty, heart-broken, and compassionate speakers. One early poem that sets the tone for the book is “I’m Trying to Write a Poem about a Virgin and it’s Awful.” In this prose poem, which comments on itself as much as on the act of writing, particularly for the audience of a writing workshop, the speaker puts her virgin “at the edge of the lake where the ducks were waddling along like Victorian children, living out their lives in blithe, downy softness.” But the virgin “hated her idleness” and “some people said I should take her out of the poem. Other people said no, take her out of the lake.” The speaker refuses both these pieces of advice: “I took her to the rush of the sea…I turned away….She wasn’t the shell I was after,” the poem concludes, owning its choices, rendering with complexity and precision the division and confluence between subject and object, self and speaker.

This spunky self-awareness pervades the collection as it engages in lively debate and conversation with poetics and art making. An expert craftsperson, Sotelo’s similes made me swoon: “the moon points out my neckline / like a chaperone,” “eyes like ice in whiskey,” and “a kind face like a clock in the country,” are just three gems. Through dramatic similes such as these, Sotelo calls attention to her performance as poet, resulting in a bravado that is at once cheeky and tender, endearing but with teeth.

Sotelo uses the motif of performance to access authenticity throughout the collection, from poems in the personas of Theseus and Ariadne, to moments in poems like “My Mother as the Voice of Kahlo,” when the speaker makes the mother a vessel through which to discuss Kahlo’s work and its relation to ideals of feminine beauty, gender, and art: “the instinct for painting is the instinct for power” and “all men are in love with themselves,” the mother in the poem warns. As the poem approaches its end, it’s harder to tell where the speaker/mother/Kahlo voices begin and end:

& even an artist

will leave his wife behind

but he can’t if she runs harder

if she’s both hunter & sacrifice

Thus, Sotelo makes the brutal argument that to be a woman artist, one must become the subject and the object—the hunter and the hunted.

Even though these poems present dark truths, they are remarkably buoyant. In “My Mother & the Parable of the Lemons,” the mother, building on sentiments in “My Mother as the Voice of Kahlo,” indicates that marriage is when “someone is always well prepared // for the sacrifice, and someone else / is the sacrifice.” This skeptical commentary on romantic entanglements pervades the collection, with Sotelo’s speakers often joking about bad luck with men: “why does the twenty-first century feel like this? / Like men are talking into / their favorite phonograph / & the phonograph is me,” she writes in “My English Victorian Dating Troubles.” These problematic power dynamics between men and women are further highlighted in the Ariadne and Theseus poems, Ariadne counseling that “when a man tells you he’s a monster, / believe him” in “Ariadne Discusses Theseus in Relation to the Minotaur.” In these rejections of and warnings about heterosexual romance, Sotelo’s speakers step fully into their power; in this way she reclaims the word “virgin,” as she seeks “versions” of self—particularly a female-bodied self—that are not defined exclusively by their relationships to men. Sotelo champions reclamation of and celebration of a self-determined identity: “I am completely in character,” she writes in “My English Victorian Dating Troubles.” It is this vulnerable confidence, the daring yet tender proclamations that Virgin offers, that transforms what might be maudlin into moxie in its examination of various wounds. It is feisty and fabulous. It makes me want a first time with it all over again.

Amie Whittemore is the author of the poetry collection Glass Harvest (Autumn House Press). Her poems have won multiple awards, including a Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Prize, and her poems and prose have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Nashville Review, Smartish Pace, Pleiades, and elsewhere. She teaches English at Middle Tennessee State University.