The Meter Reader: Tiana Clark's poems in I Can't Talk About the Trees Without The Blood "witness and embody the past"

Amie Whittemore

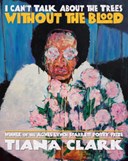

Reviewed: I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without The Blood by Tiana Clark (Winner of the Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018).

Tiana Clark’s first full length collection, I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without The Blood, is as much about race and gender (and how they intersect) as it is about the ways language intersects with race and racism, gender and sexism, self and others: “the most dangerous game, for me, is sex and syntax,” Clark’s speaker offers in “Rituals,” and, perhaps, that is because they both give birth to us: we come from sex, but we are spoken into the world, shaped by how we name the world as much as by how it names us.

This dynamic is at the crux of Clark’s powerful opening narrative poem about her hometown, “Nashville.” In it she provides a history of gentrification and systemic racism, describing how

I-40 bisected the black community

like a tourniquet of concrete. There were no highway exits.

120 businesses closed. Ambulance siren driving over

the house that called 911, diminishing howl in the distance,

black bodies going straight to the morgue.

Clark then takes us to downtown Nashville, to the “herds of squealing pink bachelorette parties,” where “someone yelled Nigger-lover at my husband. Again.” “Who said it,” her speaker wonders, searching the scene for the source; Clark also interrogates the word itself, joined—and simultaneously—broken by a hyphen that “crackles and bites, / burns the body to a spray of white wisps.” Here, and later in “Conversation with Phillis Wheatley #1,” she envisions the hyphen as the mark that embodies black history and lives in the United States, the hyphen a symbol of the slave ship on which Wheatley was born, “the scorching center of this moving hyphen— // African-American: dash exposing the break.”

For Clark as for Faulkner, “The past is not dead. It’s not even past.” The past haunts and burdens Clark’s speaker: “I carry so many black souls / in my skin, sometimes I swear it vibrates,” she writes in “Soil Horizon.” However, these connections to the past also, at times, offer solace and wisdom, particularly through the black women who populate them—which include her ancestors, Phillis Wheatley, Nina Simone, and her mother.

Several poems are “after” poems, including a sequence after dances choreographed by George Balanchine. In one, “After Orpheus,” the speaker moves from observing the dance, “Orpheus tears off his mask, the ballerina collapses / for the floor,” to internal observation:

I think about patience and its stupid song.

I can’t wait— Yes, I’m always looking back

at my dead.

As demonstrated here, Clark’s poems witness and embody the past through these deft shifts between exterior and interior observation as well as the complex use of white space, as both a disruptive and meditative tool in its slowing of the poem’s construction of meaning. Her poems are also acts of love. Her poems in conversation with Phillis Wheatley are tender, particularly when she imagines into existence a letter from Obour Tanner, “Wheatley’s only known correspondent of African descent” (“Notes”) to Wheatley:

I was a dozen broken roses, bruised as velvet,

English and reaching desire for you,

across the pews, across the vast|empty spaces, where two slaves

(who could read and write) could touch—each other—there, as women

and call it: Praise.

As this excerpt exhibits, Clark’s poems are full of lacunae and parentheticals, and often sweep across the page: they recognize the limits of speech while also resisting the forces that attempt to silence black women.

In The Art of Description: World into Word, Mark Doty writes that there is a morality to description, lying in “refusal, in that which the writer will not diminish by the attempt to supply words.” Sometimes Clark’s poems enact this refusal through white space, as in poems like “After Orpheus.” At other times, this refusal is made even more prominent through the use of brackets, as in “Dead Bug,” a poem in which the speaker tries to be witness to her own trauma, a rape she experienced as an adolescent: When I was a [ ], I spoke as a [ ], I understood as a [ ]. Here, through the combination of borrowed biblical language and empty brackets, Clark demonstrates the impossibility of articulating trauma. Her speaker reinforces this attempt in the poem’s wrenching closing image:

There is a dead cockroach in the corner.

I won’t pick it up. I keep sweeping

(around)

the thing on the floor

Thus, what’s avoided is also present: in a single life and in a country’s fraught history. You can’t ignore what is(n’t) there.

Clark’s collection is deserving of the rich praise it has already received; what I most admired is how expertly it expresses heart and mind, vulnerability and incisive intelligence. Alongside tender poems about Clark’s mother or husband, such as the lovely lyric, “Mother Driving Away After Christmas,” are wrenching indictments of racism, such as “The Ayes Have It.” The poems are also formally ambitious: “The Rime of Nina Simone,” loosely based off of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” is a powerful meta-commentary on the collection itself and its exploration of black pain; Simone tells the speaker, “they only / wanted cocktail jazz, folk, and blues, // for me to bleed negro, a signifyin(g) / monkey from my classical piano.” The speaker responds that she needs to be in her graduate poetry program, needs to “tell them when my chest tightens and flares up / when they try to conjure the other, a fantastic / field of fictitious black and brown bodies.” Clark’s speaker is urgently aware of the power of language, of whose stories get told, and by whom, and she refuses to yield that power or yield to those who would diminish her with their words. Therefore, while the collection ends with a memory of the first time someone called her the N-word, “the red hot g sounds ringing fire songs / in her ears” (“How to Find the Center of a Circle”), it is also a beginning: of claiming her voice and her right to name her pain and her triumphs, of owning her and her ancestors’ stories, and elegantly, poignantly shaping how they’re told.

Amie Whittemore is the author of the poetry collection Glass Harvest (Autumn House Press). Her poems have won multiple awards, including a Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Prize, and her poems and prose have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Nashville Review, Smartish Pace, Pleiades, and elsewhere. She teaches English at Middle Tennessee State University.