Ragged with Delight: A Conversation with Kendra DeColo

By Amie Whittemore

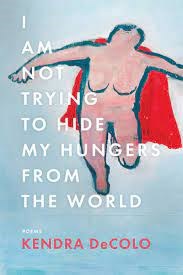

Marianne Moore writes in her ars poetica, “Poetry,” that if you demand “the raw material of poetry in / all its rawness…then you are interested in poetry.” If this sounds like you, then Kendra DeColo’s latest collection I Am Not Trying to Hide My Hungers from the World delivers: these poems maintain a raw heat while being meticulously formed; their outrageous joy and anger carried me through the pandemic—as did this slowly unfolding interview with Kendra herself. We began this conversation before she gave birth to her second child and then picked it up again many months later. In it, DeColo shares her love of the body, of food courts, and insight into the magic that unspools in her fierce, feminist poetry.

Amie Whittemore: Thank you so much for this chance to talk about your third poetry collection, I Am Not Trying to Hide My Hungers from the World (BOA Editions, 2021). I love this book: its verve, its humor, its heart, and its grit. I admire how while it roams widely across different cultural references it is always anchored in the body, to the awe that we are physical bodies, containing (and releasing) so much. So, I’d like to begin by discussing the first poem, “I Pump Milk Like a Boss,” which sets many of these themes into motion. In it, the speaker references “fermented and dank...kush,” bar bathroom graffiti, a “tattoo on my pudenda / that says Aerosmith backwards,” and yet it is also “fluorescent with prayer”:

...I know there is a price we pay for loneliness

and a price we pay to forget it and I dedicate my libido

to my younger self and this is how I want to live, milk-stained, a little bit emptied,

a little bit in love with the abundance of my body

So, my first question is how did you decide to open the collection with this poem?

Kendra DeColo: Thank you so much! “I Pump Milk Like a Boss” was a breakthrough poem for me. I wrote it after I became a mother and hadn’t written (or rather, I had been taking notes and collecting fragments) for a year and it literally gushed out of me. It was a poem that showed me a way to bring together conflicting sides—the tenderness and broke-open feeling of new motherhood alongside the feral and urgent hunger of who I am as a poet. I chose to put this poem at the beginning as a way to grab the attention of other new parents who might, too, have these opposing sides and wonder how to reconcile them in their work. I wanted the collection to begin with how I felt when I returned to writing: ragged with delight and danger.

I also love to think of the first poem of a collection as a guide or blueprint for what follows. I wanted to establish the immediate thread of taking tropes of motherhood and disorienting/reclaiming/troubling oppressive narratives that motherhood looks one particular way.

In the poem, a woman tries to seduce me by reading a sex poem while I pump. I’m only realizing now how that woman is both a real person, but another side of me—the creative and transgressive self, imploring but also guarding the mother as she gets nourishment for her child. The two can’t exist without each other.

AW: Love this response and this sense of dual and essential selves! What I admire about the first poem—and many of the poems in the collection—is how the body becomes a site of holiness; there’s a way in which the speaker rejects formal religion (admitting in “Self-Portrait as Getting Drunk-Dialed by God” that she’s “never read the Old Testament...just a half Jew / who’s never been Bat Mitzvahed”) in favor of the grunting holiness of being an animal, of her own feral essence. For instance, in “Weaning, I Listen to Tyler, the Creator,” she notes:

There is no simple way

to say I am ungovernable.

My daughter drinks & unearths

the heart underneath my heart,

feral & delicately ambushed

by the sun-smear of her breath,

my body no longer a love song

but a loudspeaker reverberating stolen time.

I feel like in this, and other poems, there is a dismantling of culturally constructed dichotomies, a refusal to believe the body is separate from the spirit, the heart from the mind, low culture from high culture. I’d love to hear your thoughts on how you see your poems doing—or not doing—this work of cultural interrogation.

KD: Yes, absolutely—I love poems that claim the body and all its funk/detritus/fluids as holy—and I wanted to especially deconstruct the false dichotomies of motherhood. It seems that we have little room in our culture’s imagination for mothers who are full and complicated characters, although there seems to be a narrative emerging now of mothers who are neither terrible or saintly, just human. Maggie Gyllenhaal, who recently directed the incredible adaptation of Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter said: “I think it's very difficult, even for adults, to hold the ambivalence of parents and mothers in their mind. And so I think we've seen lots of films and television shows where the spectrum of what's normal is pretty slim. And, in fact, I think despair, terrible anxiety, confusion, along with the kind of heart-wrenching ecstasy is all a part of the spectrum of normal.”

The experience of seeing a gap in the representation of motherhood has been very true for me and the act of writing motherhood poems that also incorporated unsavory pop culture references and profanity felt like a way of reclaiming my own story and identity. A way of pushing back against these tropes that have us all feeling like we need to be perfect mothers, which is in my opinion a kind of violence in our country: demanding perfection and criminalizing missteps without offering support.

AW: Yes to all of this, especially pushing back against problematic cultural tropes, which is a central task of the collection. For instance, there are several references to emptiness, particularly in poems dealing with giving birth as well as one of my favorite poems of all time, “I Would Like to Tell the President to Eat a Dick in a Non-Homophobic Way.” I’m curious about these constructions of emptiness. On one hand there’s the feeling the speaker has in “I Write Poems about Motherhood,” of feeling “one hollowed self opened wide // enough to swallow my own body” and on the other, in “I Would Like to Tell the President…,” that the president must eat dick, “the one he has feared his whole life // The dick that might fill the endless void inside.” What’s the difference between a “hollowed self” and a “void”? What drew you to considering absence as a feature of the self in these (and other) poems?

KD: I’ve been thinking about space these days; the kind of physical and mental space it takes to cultivate a rich interior life. Emptiness to me represents a kind of fertility, a voluptuous absence in which anything is possible and might ignite into being. The difference to me between a hollowed self and a void is that the former is part of a natural relationship to reproduction and creativity, the latter represents a kind of hostility or fear of one’s inner life (which is what I imagine is the case with 45). After my daughter was born, I was literally emptied but suddenly filled with this immense sense of self and love for her that was only possible by erasing who I had been before, which has nothing to do with physical birth but rather the act of annihilating one’s self to make room for a self that you never imagined.

I’m currently in a similar place in my life. I have a seventh-month-old baby and although the identity-shift and transition into early childhood parenting has been much less intense, I’m experiencing a fallow period which our culture tells me I should fear and reject by any means possible by filling it up with productivity. And yet I am loving this time, have walked into it with joy and openness to see who I become and where this time leads me. That actually sounds much more proactive than it really is. What I mean to say is that in all the emptiness and lack of outside commitments, I feel full, a kind of fecundity that is only possible when I let things slip away.

Maybe the pandemic prepared me for this time and so I am not afraid of being “unproductive.” I love the Ross Gay essayette “Loitering” in The Book of Delights where he writes, “It occurs to me that laughter and loitering are kissing cousins, as both bespeak an interruption of production and consumption.” In this way, I have become no one again. What I spend my days doing, taking care of a small child, is completely useless in our society (unless it translates into the consumption of expensive products to create the appearance of being a “good mother,” or ickier, the molding of a “productive” member of society.) And I am freed by it. And the joy that comes from this is absolutely terrifying to anyone who would want to control me.

AW: I’m intrigued by how pleasure—and joy, as you note—are positioned in this collection from the start with the opening epigraph from Julio Cortazar (“and let the pleasure we invent together be one more sign of freedom”) to poems in the second section, such as “pleasure not an escape / but an anchoring of the self” in “On the Cusp of 36 I Remember the Only Republican at My College Gave Me Head and I Didn’t Come.” To me, these moments, and others where sex and/or the body are richly, specifically described, point to the ability of pleasure and intimacy to empower. So, my question then is this: do you see intimacy, and perhaps writing about intimacy, as revolutionary?

KD: Yes! Being embodied, which I believe is necessary for intimacy, is revolutionary, loving my postpartum body as it is without wanting to “correct it” is revolutionary. When I think about how true intimacy and pleasure cannot be commodified, and that the prerequisite to feeling pleasure and intimacy with another person is loving oneself well—that all feels very anti-capitalist to me. I love writers whose work is embodied and centered in pleasure: Ross Gay, Patrick Rosal, adrienne marie brown, Diane Seuss. They are all revolutionary to me in different ways, but all share this feeling of pushing back against one’s tendency to feel small and instead reach for language that is juicy, hyperbolic, and rich.

AW: One of the many things I admire in this collection is the way these poems praise unlikely things; there’s a kind of reluctant jubilation toward these everyday features of living in the United States. The poems don’t read to me as ironic—though that might be a flaw in my reading—but rather as sincere, that the speaker truly does take comfort and/or joy in food courts, Costcos, and her language which is “jagged / as rocks like odes to all of the things // I have never learned, which might be the most / American thing about me” (from “Love Poem in the Style of Jordan’s Furniture”). These poems also read as anti-pastorals, as working against a tradition of “prettifying” landscape. Obviously, I’ve touched on a few issues, but I think my question comes down to this: how do you see these poems working with and against traditions in American poetry?

KD: I am relieved to hear that the poems don’t read as ironic! The speaker which is often me, truly loves Costco and food courts—so I am happy that this came across. I write a lot about fast food, the way that rest stops in particular have felt like safe psychic spaces for me during different phases of my life. A McDonald's or Wendy’s always feels like a sanctuary. Especially in New England, especially if an old Smash Mouth hit is playing through the speakers as I order my fish sandwich and coffee. I love to bring these spaces into my poems as a way of understanding my relationship to capitalism and how it affects me, but also as a way to provide a psychological respite. It makes me feel safe to imagine the plastic booths of these spaces, and I imagine that the poets who write straight pastorals find a similar sense of refuge in writing those spaces. In this way, writing about food courts feels very much connected to the American poetic traditions of understanding the self through one’s surroundings while also trying to have transcendent spiritual experiences. The departure for me is, as you said, not trying to prettify the landscape and also accepting that the spiritual can coexist with the gauche/tacky/manmade. For me, a dance party erupting in an abandoned Shoney’s parking lot after the 2020 election is beautiful on its own, and I have had truly divine moments inside Wendy’s. I love to bring that tension into the work.

AW: I Am Not Trying to Hide My Hungers from the World is (obviously!?) a feminist text. I have been rereading it alongside Sara Ahmed’s Living a Feminist Life and her examination of feminism as a way of being in the world. Ahmed writes about the tension between following given paths toward “happiness” (an idea she also considers fraught) versus taking less well-traveled paths. She writes, “feminism: how we inherit from the refusal of others to live their lives in a happy way. But our feminist ghosts are not only miserable. They might even giggle at the wrong moments. They might even laugh hysterically in a totally inappropriate manner. After all, it can be rebellious to be happy when you are not supposed to be happy, to follow the paths happily that are presumed to lead to unhappiness.” I bring her into the discussion because so often feminism is (inaccurately) associated with refusing motherhood or marriage, both things your collection celebrates (without flattening their complexities, difficulties, and emotional and physical messiness). Can you speak to how feminism has shaped you as a poet, particularly in your thinking about this collection?

KD: Feminism has always been the lens through which I write, whether asserting the right to take up space and be messy and imperfect, or writing explicitly about gender, sex work, or sexual assault. Writing motherhood feels like an extension of that, particularly the work of processing how much our society hates women, which only intensified when I became a mother. I had to work so hard to unlearn the toxic narrative around motherhood. We are given the myth that mothers are revered in our culture as well as the myth of the perfect mother who has no needs of her own.

The other side of this myth is obviously the monstrous mother—the woman who fails or resents or who asks for more. We also love stories of the monstrous mother who is punished. There was a study on our perception of women who leave their children in parked cars while running a quick errand. If the errand was something selfless, like buying baby formula or groceries, the child wasn’t seen as being in danger. If the mother got a massage, the child was immediately viewed as being in a dangerous situation. This is all to say that in order to be seen as valuable, women must completely disavow their own needs and desires—especially as mothers. And that being happy as a mother is culturally criminalized.

I experienced this in different spaces—being shamed for nursing in public, not given access to decent spaces to pump in professional settings, given dirty looks while checking out poetry books with a toddler at the library, etc. As a poet I felt the same kind of shaming and ostracization—that motherhood narratives are not welcome in certain literary spaces. This of course inspired me to push back and write poems about motherhood that couldn’t be silenced or ignored.

AW: These poems read as highly autobiographical—and fervently intimate. How do you negotiate issues of privacy and disclosure in your poetry? Or, alternate question: what is your relationship to the speaker in these poems? Where does she depart from or amplify aspects of your sense of self?

KD: The speaker in my poems is much braver than I am, maybe a little more reckless, but other than that the speaker is very much me. I also think about the speaker as being in direct conversation with certain periods of my life, as a way to validate and heal what I’ve been through, and also to honor who I was at those times. I recently listened to interviews with Jason Reynolds and Kate DiCamillo who both talked about writing explicitly for their younger selves at very particular ages. I feel that I am always writing for my 14-year-old self, not to re-parent or grieve what she suffered but rather to celebrate her wildness, the ferocity in her that allowed for these poems to exist. In this way, I feel empowered by disclosure in the way that wearing something revealing can be empowering. I am selecting what I want to show, and there is power in that discernment.

AW: I love that idea, of celebrating the past self, of letting her wildness continue to be a guide. Thank you so much for this conversation. I have one last question. I Am Not Trying to Hide My Hungers from the World came out at the “end” of the pandemic (or at least as the pandemic began to fade from many Americans’ minds). How has this impacted your experience of sharing and celebrating your work? And, more broadly, how has the pandemic impacted your practice as a writer?

KD: In the beginning of the pandemic, I started a small writing group where we met online each Wednesday to write for an hour and at the end of the session we would post our poems. I loved writing in this space and feeling connected to writers who I normally never see in person. In many ways the pandemic brought me closer to writers and artists, reminding me that writing is collective, and that urgency can exist without the need to produce, but rather, to connect. My world felt a bit bigger.

The pandemic also gave me an inner space I hadn’t had in a long time—to go deeper into healing and self-compassion which feels essential to my writing practice. Much like motherhood, the pandemic centered me in who I am outside of production, outside of the false hope of grind culture and keeping up. It gave me permission in many ways to write out of joy and to allow “pleasure to be another source of freedom.”

Kendra DeColo is the author of I Am Not Trying to Hide My Hungers from the World (BOA Editions, 2021); My Dinner with Ron Jeremy (Third Man Books, 2016); and Thieves in the Afterlife (Saturnalia Books, 2014), selected by Yusef Komunyakaa for the 2013 Saturnalia Books Poetry Prize. She is also co-author of Low Budget Movie, a collaborative chapbook written with Tyler Mills. DeColo lives in Nashville, Tennessee.

Amie Whittemore is the author of the poetry collection Glass Harvest (Autumn House Press). Her poems have won multiple awards, including a Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Prize, and her poems and prose have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Nashville Review, Smartish Pace, Pleiades, and elsewhere. She teaches English at Middle Tennessee State University.