“Self-Shaped Hole”: The Speculative “I” In Kirsten Kaschock’s Explain This Corpse

by Leah Claire Kaminski

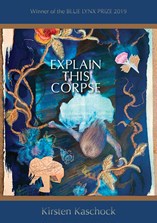

Reviewed: Explain This Corpse by Kirsten Kaschock (University of Washington Press, 2020).

To read Kirsten Kaschock’s Explain This Corpse, winner of the Blue Lynx Prize for Poetry, is to enter a sort of poetic matrix. These are not poems that give primacy to feeling, though they contain it. Their purpose seems not to be to perform or elicit emotion, as much as to use it as a tool to show us other truths. Kaschock spins ordinary material into new worlds of speculation and experience, using surrealism, language play, and metaphor so stuck-with that it feels literal: the poetic self draws herself into being along with the hyper-real world around her. In the book’s ars poetica proem, the speaker declares:

To manufacture hunger I need

time and a stick and at the end

dangling like a fish from thread—

carrot…

At the end of the short poem the diagram is sketched even more clearly:

…the stick,

the thread, my own hand holding

its famine-machine a foot beyond

the other one…

With Kaschock’s syncopated, muscular rhythms and idiosyncratic syntax, “old man carrot,” the stick, time are all made tactile, real.

Not “real” as in something encountered in the world. Real as in material. In this poem’s word-world, time is as tangible as stick, as hunger. The proem ends with the speaker saying, in her signature stylized colloquialism: “those bits I call art.” And in this collection every bit of the world—self, galaxies, politics, language—is used in service of art, which is to say in service of a moving machine (or body) that makes ideas.

Stronger-than-metaphor play with object and language recurs throughout. “The Cape was pale, and as I threw it round my shoulders, I depleted my ridinghood,” Kaschock writes in a poem that uses the speaker’s presumably literal visit to Cape Cod as a way to explore witchcraft and womanhood. Landscape, body, concept all swirling together in the field.

This book doesn’t work like any others I’ve recently read. Kaschock, an accomplished dancer as well as a writer, pinpoints her approach in an interview with Pew, where she is a fellow: “Both dance and poetry can use intimate materials (the body, the voice) to transcend individuality…The poet and the choreographer take great pains to elaborately carve out a self-sized hole through which their audience can newly perceive the universe.”

We are used to the idea of “making the personal universal” in writing, but this isn’t what Kaschock is saying, quite. It’s not “the personal” as much as it is “intimate materials,” an unsentimental mining of the very self. It’s not “words,” it’s “the voice” (meaning, the self who speaks the words too).

And it’s not “universal” but “transcending individuality”—I almost think she means the reader’s, too. The commitment to art is almost complete, and a bit intimidating.

Kaschock’s poetry scrubs out its own world to create a new one, both clear and difficult. Formal experimentation is present (not-sonnets, concrete poems, a form of ten, ten-syllable lines inspired by music in the three surreal “Circle of Fifths” poems spread throughout the book). Conversations with other poets, too (in the form of “after” poems and borrowed lines from Lerner, Atwood, Cavafy, and Bishop) betray Kaschock’s playfully formal approach. But the most consistent way her seriously playful inventiveness shows up is in her leaping technical word play, in shining evidence in “Circle of Fifths (1-3)”:

Most people are ports. Yes, some poets rape.

Navigate. Galvanize. Some prayers will die.

Most days are dry as air, dryer. Harder.

The poem ends these grinding, furious leaps with a strange and delightful punny annotation, scrambled message from an alternate universe’s classical music: “Applaudanum. Composed for one slow hand.”

The poet-speaker’s very self is a craft element. In these poems, that pesky lyric I isn’t a constant presence (at one point she writes, “The lyric I: one species of debris”): and except in the rare poem grounded literally in circumstance, it doesn’t seem to be a fixed self when it does appear, almost instead a thought experiment or one among many metaphors. Kaschock plays with language, idea, and experience like a sculptor with clay, as if it’s all uniform.

In “Dear Bird,” a poem not surreal but speculative, the speaker pushes metaphor until we’re not sure but that we should take it literally:

Feathers, in the past, have had me

coughing, stooping as I shouldered the mapled

woods, my bloody cape.

Ostensibly, this is a persona poem in the voice of a wolf, ending as it does with an unpunctuated, single-word line “Wolf.” But in the shapeshifting world of Explain This Corpse, that doesn’t really seem to matter.

Even in “personal” poems, as the love poem “Eclipse Aubade,” the book’s speaker veers between the metaphysical and the truly personal, estranging the personal images from any reliable sense of a speaker’s “self.” Here the literal domestic (“now I’m more or less happy/to drape my leg over yours/and call it married”) blossoms to something larger, stranger:

A woman needn’t have breasts

to threaten. I have knives, I’ve

pills. The moon is cold, a know-

ing leech, filling her blousy

corpse with stolens. The sun, he

miscarries, trawling the crude-

streaked skyway.

When the reasonably literal “I have knives, I’ve/pills” is linked through lineation and similar, declarative syntax to such intense personification as the moon and sun are dragged through, the reader equates, sees the poet’s world as one literally filled with miscarrying suns. Or the opposite: the poetic self is distanced, as metaphorical as that “know-/ing leech” the moon.

Or in “Exaltation,” an ode to skin is deeply physical but in the elemental, distilled nature of that physicality, also somehow impersonal:

Even as you double over, retract within me

vocals of aureole, of freckle, mold

and the worm-slash up my ankle-back

-calf where I gave unnatural loud birth to a slippery achilles, newly

twinned, eel-shredded, I accept you

unbook are my best record and home.

Obviously specific to an individual’s body, but in the extreme attention to language (“vocals of aureole”! surgery as giving “unnatural loud birth” to a tendon!) it’s galvanized into sculpture. Not transparent confession but a bas-relief of the self.

The book, as its title would indicate, is chock-full of corpses. The moon, the world’s species, the speaker, Ophelia (in the book’s title poem), capitalism, bodies eaten by deer: all aging, dying, or near death. Even an imagistic lyric about nightfall becomes apocalyptic. But, except when discussing climate change, the speaker is not death-obsessed in any romanticized, depressed, or hopeless way. It’s death as engine for life. Death as companion to life. And life ripples through these poems. The two converge, and the emotion underscoring the formal intelligence of this book erupts, in “O Nibiru,” a 30-page poem comprising the book’s middle section.

Here Kaschock dives deeper into the book’s fascination with death, or even more than death, extinction: “a hard rain of trailing comets…will obliterate us” she says. And later, “If at all moments we faced certainty not of single end but scorched sphere, we might alter the ways we attempt to translate ourselves into the future.” It’s not just climate change and world-ending collision, though. This is a deeply personal poem—a large, self-shaped hole in the center of the book, a deeply earnest (though inescapably intelligent) go at “translating herself.”

The speaker’s conversation about climate destruction and obliteration with the world-ending (and apocryphal) “planetary object” Nibiru mixes with day-to-day musings about mothering and leaving, about standing at the sea, about the girl the speaker never had, about phones and mothers, and occasionally the two threads collide:

There is some deep crevasse in me that hikers have fallen down.

But I am melting, I am melting.

The poet become an entire, imperiled landscape, poked with death and sex and literature and philosophy. Crawling with them, as is the world. “Must I be so outside I’m theoretical?” she asks. In Kaschock’s particular, hard-nosed alchemy, her poems use elements of language as tools to contort her very poetic self, until the voice becomes a body, twisting, leaping, into flight.

How limitless, how tangible, how strange.

Leah Claire Kaminski is the author of two chapbooks: Root (Milk and Cake Press, 2022), and Peninsular Scar (Dancing Girl Press, 2018). Her poems and prose appear in Fence, Massachusetts Review, Prairie Schooner, Quarterly West, ZYZZYVA, and elsewhere. Winner of the Summer Literary Seminars Grand Prize and finalist for the WICW fellowships, she lives in Chicago.