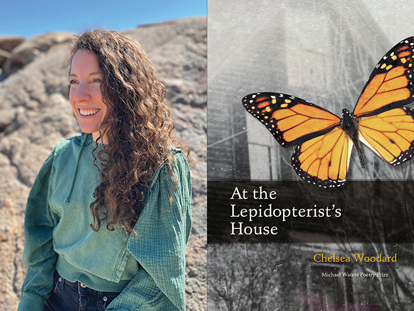

Interview by Lisa Fay Coutley

Lisa Fay Coutley: I’m so glad I had the chance to spend good time with At the Lepidopterist’s House. This lovely and aching collection opens on various ways of wishing for that which can’t be (the hope of returning a skeleton to its original form; stripping birds of flight; winged things in a glass world; even the dog longs for elsewhere), and where these wishes are imagination, they are also constraint. Can you say a bit about the well from which those trapped wishes came and how they fueled this work?

Chelsea Woodard: What an interesting question. I think that one of the governing forces in the poems is nostalgia, which is of course a longing for what is no longer accessible—that “suffering or grief” (algos) from the inability to “return to native land” (nostos). I am interested in what people do in the face of time and change and factors outside their control and the ways in which they seek to reassert control or regain some element of the past. I think creating art is one of these coping mechanisms, and in some ways, all of the characters in the first section of the book are doing that—seeking to understand or organize their experience or the world around them into a shape that makes sense to them. You could also say that art is always elegiac, always memorial. You could say this about poems. I’m thinking of Hass’s “a word is elegy to all it signifies.” So, in some ways, these poems are about reclaiming lost things, or trying to prevent their loss. But I also think that works of art are affirmations as much as they are memorials—of love and of living presence. In that way, maybe the poems are all love poems as much as they are poems of loss.

LFC: That’s a lovely way to frame it. Early on there’s so much fracture and nostalgia and attempts to reassemble within lyrically charged images. You lean into rhyme and form here early and often. What was the process of arranging this work? Did form and music allow you to make your way into (and to sustain) this particular content, which grows more vulnerable page-by-page, section-by-section?

I have always been a formal poet, and I do find formal constraints to be creatively freeing.

CW: This is a really good question. The poems in the first section are, in general, the earliest poems in terms of when they were written. I have always been a formal poet, and I do find formal constraints to be creatively freeing. I also think there was something to these voices and subjects that lent themselves to more formally aware poems. I almost always let the idea for the poem dictate the form, so that it is organic, and these poems came about that way. I also think, that as the poems get more personal, perhaps the forms become more experimental or looser. Sometimes, though, I lean on a form when I need some rigidity to talk about something difficult, as in the poem “Home Inspection,” with rhymed quatrains. In that poem, the form sort of helped me keep it together. Then, in a poem like “In the Matter Of,” the repeated legal phrase and anaphora itself became a structure and a form—another constraint and propeller that I felt I very much needed to communicate the experience of divorce. I think that life sort of unfolded, and the poems moved from persona-based poems to those rooted in my real life, thereby becoming less reliant on artifice and a bit more stripped down.

LFC: Just as you might use form to enact content, or to find the way through, in grief, the mind tries to organize what it can, and while we know there are not five neat stages of grief, despite Kübler-Ross, you do employ five sections, each grieving. Did you hear grief’s perceived stages echoing as you drew speakers who collect, assemble, wish, grieve, and try to hold on while letting go?

CW: You know, I didn’t even think about the stages of grief as I was organizing the collection, but it is such a good observation. I do think that collecting is a response to, or coping mechanism for, the losses inherent in living. My ex-husband and I grew very interested in minimalism about five or six years ago, and as I started to examine my own relationship to things, I became very interested in how material things were collected or otherwise stored meaning for others. I am thinking of Wordsworth in “The Prelude” right now when he has lost both of his parents and he writes, “I was left alone. Seeking the visible world...” I think in those moments of loss and bereftness, sometimes we take comfort in the things we can look at, touch—hoard, even. I was very interested in Eris, whose voice appears in the final section, as a sort of antidote or response to the clinging. In casting off others’ expectations and former versions of herself, she is free, “sheltering nothing.” We all know that clinging (to the past, to anything other than what is) brings suffering. She rejects that. To me, this is such an image of freedom. I wanted her to take up space at the end of the book.

LFC: The seeking here is palpable, to be sure, and pain and grief are indescribable at any age, though especially for the young. In “Double-Portrait: Migraine,” you write: “As a child, I could never / understand how a body could turn on itself / make her lie corpse-straight and as still / as the winter lake.” The image shifts from dread to stillness in what seems an attempt at sense-making, hinging on the turn that a line break allows. Can you say a bit about your process in drafting and revising this work? Did these poems offer you a space to try to understand, or to give shape to what’s indescribable, or to reshape what can’t be changed, or…?

I think we are really lucky as poets to have this gift of being able to witness our experiences, and maybe understand or come to terms with them better through this creative process. Sometimes it’s hard, but in those times of real grief, I have felt grateful to be able to see and articulate what has felt unbearable or unsayable.

CW: I follow The Paris Review’s Instagram account, and love seeing the interviews they post. I was reading one of these recently with Richard Wilbur, where he said that “One of the jobs of poetry is to make the unbearable bearable through clear, precise confrontation.” I love this, and it resonates a lot with the poems I’ve been writing over the last two or so years. I’m a yoga teacher, and in yoga, we talk about the vijnanamaya kosha, the witness body, sometimes accessed through meditation, that allows us to see and make sense of our own thoughts. I think we are really lucky as poets to have this gift of being able to witness our experiences, and maybe understand or come to terms with them better through this creative process. Sometimes it’s hard, but in those times of real grief, I have felt grateful to be able to see and articulate what has felt unbearable or unsayable.

LFC: In this excavation and memorialization—in various forms/structures, different arrangements of rhyme/sound, mythical characters, literary figures, constructed selves, nature, artifice, winged things, water in all forms, ghosts—there are so many kinds of bodies. What tethers them all in your conception of the collection?

CW: I think artistic and scientific pursuits are about searching—for deeper truths or beauty, even, which is a form of truth. For me, when I realized what the book’s title would be, I also understood the central themes and questions that would tether the collection. The lepidopterist is of course Nabokov—scientist and artist, constantly searching and recording, constantly gesturing in exile towards home—but it is also me, looking at nature and animals, looking to artistic making and trying to understand loss, and the body, and myself. The searching, observing, and making are all embodied in the lepidopterist’s practice: going out into nature—like Nabokov’s Aurelian plans—to find the butterflies, to watch them, then catch them, mercilessly preserve them, and even draw them. It is a searching, loving, meticulous, and nostalgic pursuit. To me, this really resonated artistic processes, especially poetry. Then of course, there is the house (the house on the book’s cover is actually an image of the house I grew up in)—the concept of home, domestic life and marriage, the bonds that tether us in good and difficult ways. The book has some opposing energies in its sections, too (ephemera, which are fleeting, and mementoes, which are stored and presumably lasting). I hope that, ultimately, the collection and poems find a balance.

LFC: They certainly do, and in the final poem, there’s acceptance, which leans more toward hope than despair. How do you balance readers’ expectations of grief (and the need for hope) with the experience of grieving (on the page)? Do you feel compelled to end closer to the light than the dark, no matter how organic/orchestrated?

The more I live, the more convinced I am that our human experience is never one thing or the other; you can experience deep, doubling-over grief, and also deep beauty and bubbling joy.

CW: I thought about this a lot when revising the manuscript, and what note to end with. I was thinking about Claudia Emerson’s beautiful Late Wife, and how the final poem lifts and resonates with the rest of the book—acknowledging the precarious fate of the turtle, but also rejoicing in life and moments of hope. This book originally ended with a different poem, but as the collection evolved and life happened, the ending poem didn’t feel true to how I felt or where the poems were leading anymore. I also wanted the book to be closer to my experience, which has been so much of “this and” not “this but.” The more I live, the more convinced I am that our human experience is never one thing or the other; you can experience deep, doubling-over grief, and also deep beauty and bubbling joy. These happen in congruence, not isolation.

I had a travel plan that I had to cancel, and through which I had hoped to write a new poem for the end (at Nabokov’s grave in Montreux, to complete the “Resting Places” section). But I had had something that was physically and emotionally very traumatic happen a few months before and was in bad shape and couldn’t go. I was upset, both for the inability to travel and the loss of the poem. But then, last winter, about six months after winning the book prize, I realized that maybe the not going was the poem, and I remembered my favorite story by Nabokov, that I love to teach and always read as autobiographical: “A Letter that Never Reached Russia.” I knew that that was the poem—the letter that is written but never reaches, the gesture towards somewhere maybe unreachable but reached for anyway. I felt I had come out on the other side of something deep and wrenching that made me really look at my soul (have you ever looked at your soul? I’m not sure that I really had). It made me know my soul better, maybe for the first time—when it was light-filled and when it was screaming—and I wanted that song to be the last one. It felt true and pure in ways that were important, that are important.

Lisa Fay Coutley’s collections include: HOST (Wisconsin Poetry Series, 2024), tether (BLP, 2020), Errata (SIUP, 2015), In the Carnival of Breathing (BLP, 2011), Small Girl: Micromemoirs (Harbor Editions, 2024), and the anthology, In the Tempered Dark: Contemporary Poets Transcending Elegy (BLP, 2024). She is an NEA Fellow, associate professor of poetry and creative nonfiction in the Writer’s Workshop at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and Chapbook Series Editor at Black Lawrence Press.

Lisa Fay Coutley’s collections include: HOST (Wisconsin Poetry Series, 2024), tether (BLP, 2020), Errata (SIUP, 2015), In the Carnival of Breathing (BLP, 2011), Small Girl: Micromemoirs (Harbor Editions, 2024), and the anthology, In the Tempered Dark: Contemporary Poets Transcending Elegy (BLP, 2024). She is an NEA Fellow, associate professor of poetry and creative nonfiction in the Writer’s Workshop at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and Chapbook Series Editor at Black Lawrence Press.